“There is no conflict between science and religious belief,” he once told a television interviewer. “My faith is enriched by my science, and my science enriches my faith.”

Father Coyne rejected the view that science is the only way to true and certain knowledge, but he also challenged religious fundamentalists and proponents of the intelligent design movement, which he said reduces God to a “dictator God … who made the universe as a watch that ticks along regularly.”

In 2005, he published an essay, “God’s Chance Creation,” in the Catholic magazine The Tablet in response to a New York Times op-ed by Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, a prominent proponent of intelligent design.

“God in his infinite freedom continuously creates a world that reflects that freedom at all levels of the evolutionary process to greater and greater complexity,” Father Coyne countered. In an evolutionary universe, he wrote, God, like a loving parent, “is not continually intervening, but rather allows, participates, loves.”

Similarly, he challenged his friend Stephen Hawking, the Cambridge University physicist who wrote in A Brief History of Time that when scientists finally come to understand the formation of the universe, “it would be the ultimate triumph of human reason—for then we would know the mind of God.”

Father Coyne described Hawking’s concept of God as “something we need to explain parts of the universe we don’t understand. I tell him, ‘Stephen, I’m sorry, but God is a God of love. He’s not a being I haul in to explain things when I can’t explain them myself.”

George V. Coyne was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1933. After attending Loyola Blakefield, a Jesuit high school in Towson, Maryland, he entered the Society of Jesus in 1951. “They threw out the fishing net,” he once joked, “and I didn’t know any better.”

At the Jesuit novitiate in Wernersville, Pennsylvania, a professor of ancient Greek and Latin literature helped turn him on to astronomy, providing him with books on the subject and a flashlight so he could read them in bed after lights out. “It was forbidden fruit,” Father Coyne told The Catholic Sun in 2012, “but it was good fruit!”

He continued his studies at Fordham, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and a licentiate in philosophy in 1957. Five years later, he earned a doctorate in astronomy at Georgetown, where he studied the chemical composition of the moon. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1965 and soon after that joined a team of researchers at the University of Arizona who were mapping the surface of the moon—something Jesuit scientists had been doing since the mid-17th century. Their research helped guide NASA as it planned the Ranger missions and Apollo crewed missions to the moon during the 1960s.

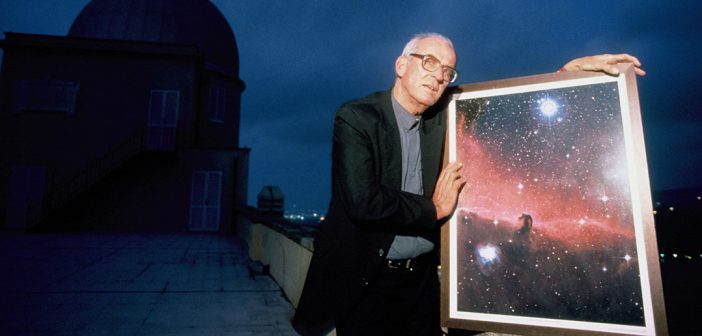

Father Coyne later focused his research on the life and death of stars, especially binary stars, and the evolution of protoplanetary discs, among other topics. He published more than 100 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals. In 2009, he received the George Van Biesbroeck Prize from the American Astronomical Society, and an asteroid—14429 Coyne—was named after him.

Brother Guy Consolmagno, S.J., the current director of the Vatican Observatory and a former Loyola Chair in Physics and Astronomy at Fordham University, was a graduate student at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Lab in the 1970s when he first met Father Coyne. They later worked together at the Vatican Observatory.

“His instructions to each of us upon arriving at the observatory [were] simply: ‘Do good science,’” Consolmagno said at the funeral Mass for Father Coyne, held on Feb. 17 at LeMoyne College. “The science itself was the goal. And he gave us the space to make it happen.”

Under Father Coyne’s leadership, the Vatican Observatory expanded from its traditional base at Castel Gandolfo south of Rome to a second site on Mount Graham in Arizona, where in the early 1990s he presided over the installation of the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope, or VATT. He founded the Vatican Observatory Summer School, a research academy for graduate students, creating opportunities for women to become affiliated with the observatory research staff for the first time.

From 2006 to 2011, he served as president of the Vatican Observatory Foundation, and for the past eight years he held the McDevitt chairs in religious philosophy and physics at LeMoyne College, where he taught courses in astronomy, cosmology, and the relationship between science and religion.

Father Coyne often described parallels between science and religion while maintaining that they are independent pursuits. The Bible, he often noted, predates modern science, which he saw as neutral, a discipline that doesn’t have theistic of atheistic implications in itself.

In a 2010, Father Coyne and Consolmagno were interviewed by Krista Tippett, host of the NPR show On Being. Father Coyne spoke about the temptation to imagine a “God of the gaps.”

“We tend to want to bring in God as a God of explanation, a God of the gaps. … Newton did it,” he said. “If we’re religious believers, we’re constantly tempted to do that. And every time we do it, we’re diminishing God and we’re diminishing science. Every time we do it.”

He said that his belief in God and his scientific knowledge led him to consider, “What kind of God would make a universe like this?”

“I marvel at this magnificent God,” Father Coyne said. “He made a universe that I know as a scientist that has a dynamism to it, it has a future that’s not completely determined. … This is a magnificent feature of the universe.”

“My knowledge of the life and death of stars,” he added, “leads me also to know that there’s a unity, a whole universe with respect to life and death. If stars were not being born and dying, we would not be here. The sun is a third-generation star. It was only after three generations of stars that we had the chemical abundance to make an amoeba, to make primitive life forms, and through that to come to ourselves.”

He said his religious faith, like science, is something that he worked at constantly.

“Every morning I wake up, I have my doubts, I have my uncertainties, I have to struggle to help my faith grow, because faith is love,” he said, and “love in marriage, love with friends and brothers and sisters is not something that’s there once and for all, and always kind a rock that gives us support. And so what I want to say is ignorance in doing science creates the excitement in doing science, and anyone who does it knows that discoveries lead to a further ignorance.”

Ultimately, he said, “Doing science to me is a search for God, and I’ll never have the final answers, because the universe participates in the mystery of God. If we knew it all, I’d sit under a palm tree with my gin and tonic and just let the world go by.”