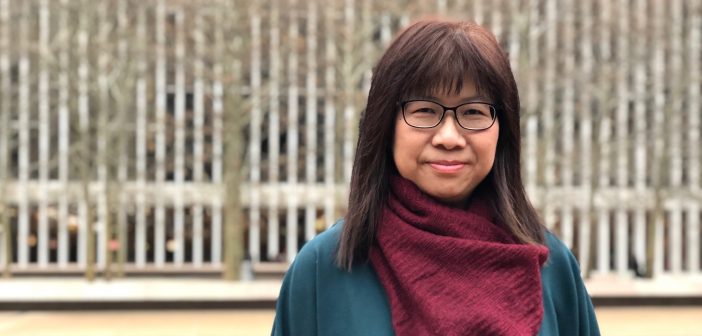

These are the questions that Imelda Lam, Ph.D., GRE ’15, faces every day.

Lam is a curriculum developer in the Catholic Diocese of Hong Kong’s Religious and Moral Education Curriculum Development Centre, a group that produces teaching and learning content for religious schools and provides professional training for religion teachers. In 2006, she began writing religious education textbooks for Catholic schools across Hong Kong. Lam and her colleagues create content for both teachers and students, including instruction guides, lesson plans, PowerPoints, audio files, and videos. So far, they’ve developed textbooks for children ages 4 to 15, and they’re currently working on books for older teens.

Their textbooks touch on topics like love, ethics, temptation, and moral decision-making. Lam’s team selects the stories, activities, and biblical references that make it to publication—and it’s no easy feat. Lam says, for example, she has struggled with choosing the right words to talk about premarital sex, which Catholic teaching says shouldn’t happen.

“But why? How do you guide them [students]to think about that?” she said.

Lam, a Hong Kong native, began working at the Religious and Moral Education Curriculum Development Centre in 2006. That same year, the Catholic Diocese of Hong Kong released its first centralized curriculum for Catholic schools. It became the guiding point of the material that Lam and her colleagues use in their religious education textbooks.

After a few years, her life changed. Lam, who had previously been a primary school teacher for more than a decade, wanted to become an educator for religion teachers. She also realized that if she wanted to create the highest quality teaching aids for educators and their students, then she needed to strengthen her skills and continue her own education.

In 2011, Lam enrolled in the religious education Ph.D. program at Fordham’s Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education. She says the most useful thing she learned at Fordham was a deeper style of teaching. In Hong Kong, many religion teachers educate their students by reading stories from the Bible, singing songs, praying, and creating arts and crafts. But Fordham taught her that this is not enough.

“To teach religious education is to have them have a bigger mind,” Lam said. “To understand the meaning of life, and to think about Christian values.”

Their current curriculum is no longer limited to activities like storytelling and singing. Lam says religion school teachers are now more focused on providing reflective activities, like encouraging students to share their own experiences and the lessons they learned. Then they, in turn, can model this behavior when teaching their young students.

Let’s say a teacher is talking about the concept of forgiveness, Lam said. She might have them reflect on when they’ve been angry with someone, and vice versa. Did they forgive them? Have they been forgiven by someone? How did they feel? They can bring this reflection back to their work in the classroom.

“Children learn by experience,” said Lam, who is also a part-time lecturer in teacher training at the Caritas Institute of Higher Education, a post-secondary college in Hong Kong. “Learning through their own experiences and other’s experiences leads them to think bigger, and think more about life and values.”

Nearly half of Hong Kong’s Catholic schools—150 out of 270—have adopted the local Catholic Diocese’s curriculum, Lam estimated. Most of the students in these Catholic schools are not Catholic. But everyone can learn something from a Catholic education, just like at Fordham, she said. In other words, a Catholic style of teaching can help the younger generation become thoughtful citizens and make wiser decisions in their lives.

“When you are growing up, you need to make decisions every day, every minute—to choose what to do, to choose a boyfriend, to make a family,” she explained. “Why don’t we teach the young guys [students]to know how to choose?”

“We don’t force them to accept Christian values,” she emphasized. “But at least they have the chance to know them: how to reflect on being a better person, how to have a bigger dream, how to have a meaningful life.”