On Aug. 26., in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the state restrictions on mass gatherings, fall classes at the University commenced under the auspices of a brand-new flexible hybrid learning model.

The model, which was laid out in May by Dennis Jacobs, Ph.D., Fordham’s provost and senior vice president for academic affairs, is designed to be both safe and academically rigorous. After being forced to pivot to remote learning in March, professors and instructors, aided by Fordham’s IT department, spent many hours this summer preparing to use this model for the fall.

Today, some classes are offered remotely, some are offered in-person—indoors and outdoors—with protective measures, and still others are a blend of both. Whatever the method, professors are engaging students with innovative lessons and challenging coursework.

Rethinking an Old Course for New Times

Barbara Mundy, Ph.D., a professor of art history, said the pandemic spurred her department to reimagine one of its hallmark courses, Introduction to Art History. The course, which covers the period from 1200 B.C. to the present day, is being taught both in-person and in remote settings to 327 students in what’s known as a “flipped” format.

Before classes are held, students are provided with pre-recorded lectures, reading material, and videos, such as Art of the Olmec, which Mundy created with the assistance of Digital and Visual Resources Curator Katherina Fostano and her staff. When students meet in person or via live video, they then discuss the material at length. The content was changed as well; it now also addresses the representation of Black people throughout history and showcases artists who tackle themes of racism.

“Because we were looking at a situation where we couldn’t just do business as usual, I proposed that we take this moment to really rethink our intro class, which we’ve been teaching for decades,” Mundy said, noting that the department has expanded in recent years to include experts in art from more diverse sections of the world.

Contemplating the Bard

Before the COVID crisis, Mary Bly, Ph.D., professor and chair of the Department of English, presented materials to students in her Shakespeare & Pop Culture class and encouraged them to generate their own ideas on them during live discussions. Now she breaks her students up into pairs, and later “pods,” of about six students on Zoom, to form a thoughtful argument about a particular work of art, video, film, or theater.

“An argument is not a description,” said Bly. “It has to have some evidence or context to make their argument, say, for example, ‘This film is a racist portrayal of the play for the following reasons,’ or, ‘The director of this film pits the values of pop culture against Shakespeare and the British canon.”

To propel the conversations, she created a series of video-taped lectures with Daniel Camou, FCLC ’20. In some cases, students are expected to respond with a video of their own.

Embracing New Technologies

Paul Lynch, Ph.D., an associate professor of accounting and taxation at the Gabelli School of Businesses, is teaching Advanced Accounting to undergraduates and Accounting for Derivatives to graduate students this semester. Of the five classes, four are exclusively online, and one is exclusively in person. For his remote classes, he’s turned to Lightboard, which allows him to “write” on the screen. He jokingly refers to it as his Manhattan Project.

“I love being in the class with the students. I enjoy the interaction, and I thought that was missing,” he said. “This gives me the ability to let the students see me as if I was in class writing onto a transparent whiteboard.”

He said he hasn’t had to change much of the content. The only major difference now is that instead of passing out equations on printed paper, he emails students custom-made problems in PDF format, and then edits within that document after they’re sent back.

“I’ve always given them take-home exams, and always worked off Blackboard, so it’s just a natural extension of what I used to do in class,” he said.

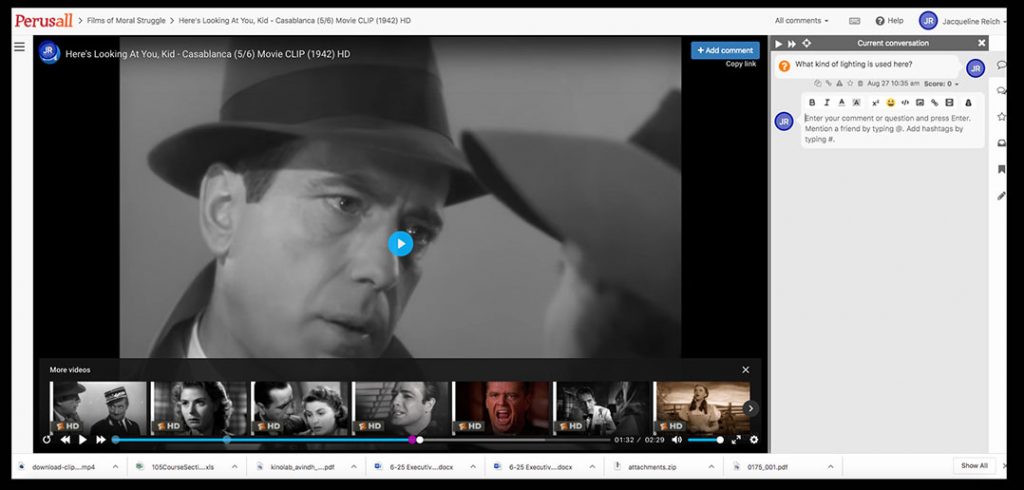

In Jacqueline Reich’s class Films of Moral Struggle, students are using the platform Perusall to examine how films portray moral and ethical issues. They watch and analyze films like Scarface, a 1932 movie about a powerful Cuban drug lord, and The Cheat, which shows the early representation of Asians in American films, said Reich, a professor of communication and media studies.

Among other things, students can use Perusall to annotate scenes from movie clips, such as the classic film Casablanca, where they identified shots ranging from “establishing” and “reaction” to “shot/reverse shot.”

“It’s a really good exercise to do in class when you’re teaching film language or talking about editing or lighting, because students can pause and comment on a particular frame,” Reich said.

She meets with 11 students on Zoom on Thursdays and another eight in person at the Rose Hill campus on Mondays.

In another virtual classroom, Peggy Andover, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology, is teaching undergraduates at Rose Hill how the laws of the environment shape behavior in an asynchronous class called Learning Laboratory. Andover said that platforms like Panopto, which transcribe her lessons, can make it easier for students to look for specific information.

“Let’s say you’re studying for an exam, and you see the word ‘contiguity’ in your notes, and you don’t remember what it means. You don’t have to watch the entire lecture again—you can search for ‘contiguity’ and see the slides and the portion of the lecture where we were talking about it,” Andover said.

Graduate students teaching in the psychology program are also using Pear Deck to make their virtual classrooms more engaging on Google Slides, she said.

“You have this PowerPoint that’s being watched or engaged in asynchronously, but [Pear Deck] allows you to put in interactive features,” including polls and student commentary, she said.

“Our grad students found it’s a way to really get that engagement that they would potentially be missing when we went to online learning.”

Learning from Classmates

Aaron Saiger, a professor at the Law School, made several adjustments to Property Law, a required class for all first-year law students. Instead of meeting in person twice a week for two hours, his class of 45 students meets on Zoom three times a week for 90 minutes, an acknowledgment that attention spans are harder to maintain on Zoom.

The content is the same, but the way he teaches it had to change. While he was able to record four classes’ worth of lectures to share asynchronously, that wasn’t an option for everything.

“I’m spending less time talking to students one-on-one while everyone else listens, which is the classic law school teaching mode; we call it the Socratic method,” he said. “Everyone else is supposed to imagine that they’re the person being called on.”

Saiger’s solution is having students share two-sentence answers to questions in the Zoom chat function to gauge what everyone’s thinking about a topic, having them do more group work, and leaning more on visual material.

“The difficulties are not insubstantial, but I think we are meeting the challenges and finding a few offsetting advantages that will make it a good semester for everyone.”

Getting Creative with Lab Work

Stephen Holler, Ph.D., associate professor of physics, holds most of his experimentation class in person, with a few students attending remotely.

The in-person group is working on a hands-on solar project that allows them to learn about the material, electric, programming, and optical components of physics.

Students who are attending the class remotely are doing related mathematical work as a part of their semester-long project.

“One student is studying interference coding in optics, so I have him looking at designs in a paper,” he said. “He’s learning all the underlying physics for what goes into a portion of these mirrors that are used in laser systems.”

His students will be conducting experiments at home instead, using kits he’s sent them.

Christopher Koenigsmann, Ph.D., assistant professor of chemistry, is sending lab kits to the students in his general chemistry class so they can conduct experiments from home.

“We were between a rock and hard place—you can’t have the kids in the lab, and at the same time, we can’t not have some kind of hands-on,” he said.

The kits will allow students to participate in labs virtually through a Zoom webinar with their professor, as well as in breakout rooms with their lab teams.

“We adapted as many of our experiments as we could to just use simple household chemicals that are all completely safe,” he said.

Elizabeth Thrall, Ph.D., an assistant professor of physical and biophysical chemistry, likewise sent a kit to students that they can use to build a spectrometer. Students can build it out of Legos, using a DVD and a light source to create different wavelengths of light. They capture them using their computer’s webcam which processes the data. They will then design an experiment that everyone in the class will conduct.

“Designing an experiment so that you learn something, that answers the question you set out to answer, and gives a protocol that someone else can follow so they can get the same results that you got, is really at the heart of what it is to do scientific research,” she said.

—Taylor Ha, Kelly Kultys, and Tom Stoelker contributed reporting.