But that year was a heady one, for both McLuhan and for a nation that would soon undergo profound cultural and political changes, panelists said on Oct. 13 at Fordham.

The University and New York City served as twin incubators for the Canadian philosopher and new media scholar’s always evolving theories, said McLuhan’s son, Eric. “It was a magical year,” he said. “Everything we predicted in ‘67 or ‘68 has come true.”

Global Interconnectedness

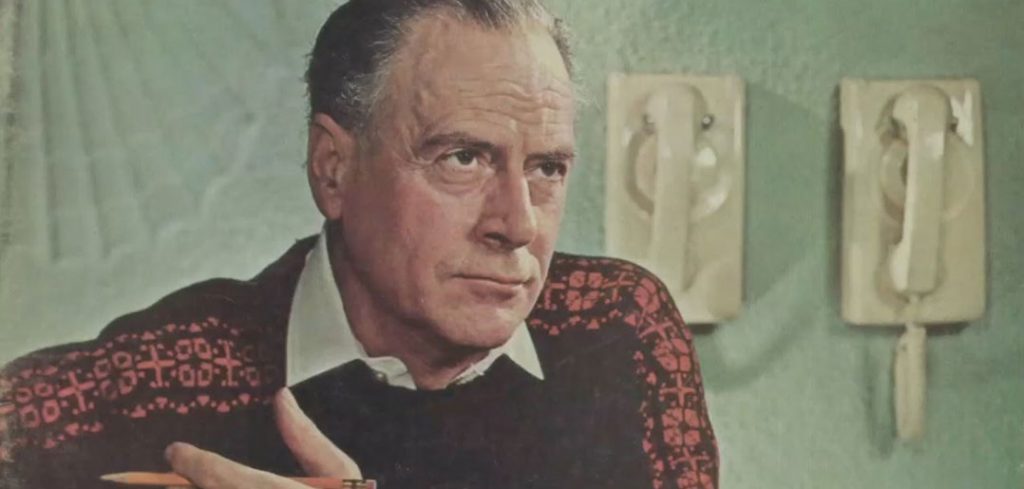

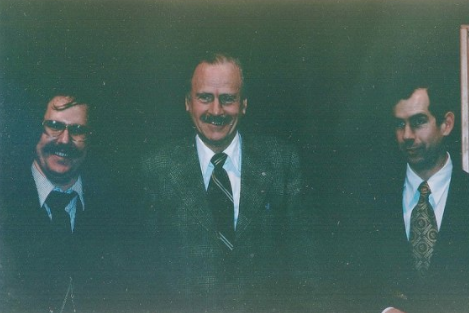

Eric McLuhan joined two of his father’s protégés—Fordham communication professors John Carey, Ph.D., and Paul Levinson, Ph.D.,—at the Lincoln Center campus for a look-back, on the 50th anniversary of McLuhan’s tenure at the University. He referenced his father’s conception of the global village, a term the elder McLuhan coined to denote the interconnectedness of people throughout the world via ever-evolving technology; i.e., what became known decades later as the World Wide Web.

That particular academic year, McLuhan and his team of collaborators—son Eric, University faculty member John Culkin, S.J., the painter Harley Parker, and the anthropologist Ted Carpenter—conducted seminars, showed films, and assigned independent projects to students that would echo and expand on McLuhan’s thinking. His ideas about technology and society were most conspicuously outlined in his aphoristic declaration that “the medium is the message.” For the students and their mentors, the semester amounted to a theater of experimentation, exploration, and prognostication.

Eric McLuhan suggested that his father’s prescience continues to resonate today, 37 years after his passing. It has never been more evident during an epoch when “fake news,” “media bubbles” and “social media” dominate the discourse, panelists agreed.

A Million Isolated Villages

Carey, who studied under McLuhan, recalled an instance when McLuhan said his theories were works in progress. “He said, ‘Don’t take everything I say as gospel. A lot of what I say I’m just testing the waters and I may disagree with myself a week later,’” Carey said.

He suggested that McLuhan would likely have revised his conception of the global village given the ubiquity of the internet, which McLuhan had foreseen some 30 years before its advent.

“He talked about the fact we were in a global village, that essentially we were all getting the same thing and that meant we were one village even though we were the world,” Carey said. “I think the Internet has totally shattered that. We’re not in a global village anymore. We’re in a million isolated villages of our own choosing. And I think he would observe that were he here.”

Inside Looking Out

(From McLuhan in an Age of Social Media)

Although McLuhan’s tenure in the media capital of the world was short, it shaped him profoundly, his son said. From his home base in Toronto, McLuhan was able to peer into the United States regularly and see his neighbors “more clearly than the people involved in it could see themselves.”

“Now he found himself on the inside looking out, and he learned a lot,” he said.

Levinson, the author of Digital McLuhan and McLuhan in an Age of Social Media (the latter first published in 1999), said McLuhan was always probing. He was a person who declined to make value judgments, preferring instead to keep exploring.

During a Q and A, Levinson was unequivocal in response to a questioner asking who, today, has inherited McLuhan’s mantle as a far-sighted inquisitor.

“It’s ipso facto impossible for there to be another McLuhan,” Levinson said.

–Richard Khavkine