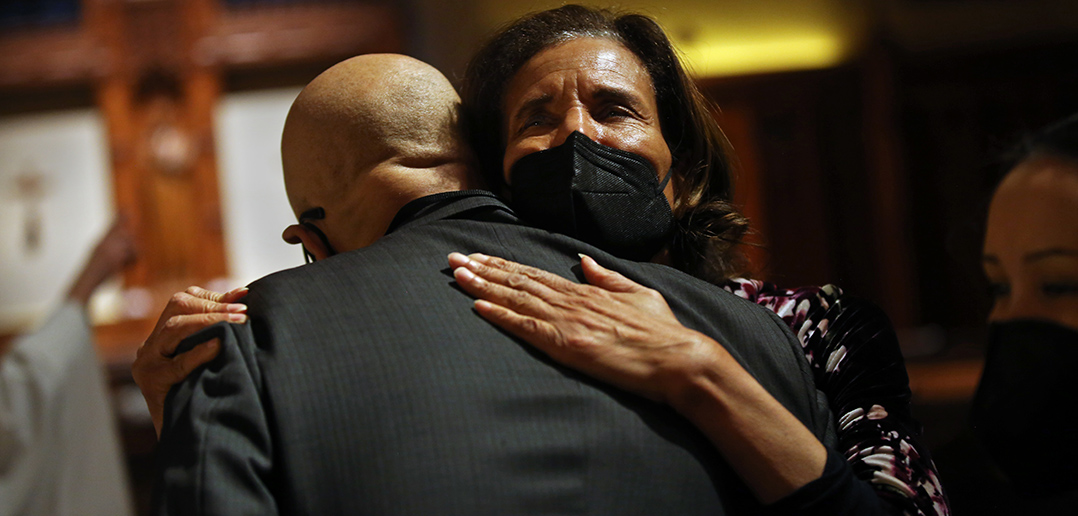

Dean Stovall’s widow, Denise Herd, embraces his cousin Jack Smith at the memorial.

Laura Auricchio, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center, was the first to share her memories of Stovall. Auricchio sat on the search committee to recommend a new GSAS dean in 2020. Like Stovall, she is a scholar of French history, so his name stood out for her among the many applicants.

“I am not exaggerating when I tell you that I leapt out of my chair, I raised my hands over my head, jumped, and let out a loud, ‘Yes!’” she recalled. “I recognized the name, Tyler Stovall, as a recent past president of the American Historical Association, as well as a groundbreaking scholar of French history, given my own work on French-U.S. connections, and I had particularly admired Tyler’s 1996 book Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light.” (Houghton Mifflin).

Eva Badowska, dean of faculty of arts and sciences and associate vice president for arts and sciences, reads Maya Angelou’s “When Great Trees Fall.”

Indeed, Stovall’s accomplishments were formidable. Just last year he published the latest of his 10 books, White Freedom: The Racial History of an Idea (Princeton University Press, 2021). The last of his numerous articles was published in The Nation this past October, focusing on the relationship between authoritarianism and democracy. Before Fordham, he was dean of the Humanities Division and a distinguished professor of history at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and the dean of the Undergraduate Division of Letters and Science at the University of California, Berkeley.

When she realized Stovall was a candidate, Auricchio said, she had only one concern.

“Would he actually come?”

Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham wondered the same.

“I had the same reaction Laura had, all of that academic brass, would he come to Fordham?” he recalled.

Father McShane said that Stovall’s academic acumen was equally matched by his accomplishments as an effective administrator during his many years at the University of California.

FCRH Dean Maura Mast reads the intercessory prayer.

“I could not believe our good luck in attracting him to Fordham or our good luck that God put it in his heart to choose Fordham,” he said.

Father McShane said that when Stovall arrived, virtually at first due to the pandemic, the University community soon discovered he was a man of “great graciousness and grace.” Citing the afternoon’s gospel reading from the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:1-12a), Father McShane called Stovall, a “man of the beatitudes.”

“Although he possessed a towering intellect, he wore all his many honors quite lightly,” said Father McShane. “He was rightly hailed for his many academic accomplishments, but he was also a serene and supportive and joyful colleague to us all.”

And, for a time, he was also a neighbor, said Rafael Zapata, Fordham’s chief diversity officer. Zapata said that at the start of the pandemic he often Zoomed with Stovall while sitting in Riverside Park. It was a serene backdrop that aroused Stovall’s curiosity. Zapata was soon helping Stovall find an apartment nearby, which also happened to be just north of Auricchio’s neighborhood. There, Stovall dined with Fordham colleagues at what soon became favorite spots to meet, such as Fumo, an Italian restaurant in Harlem, where Zapata ran into Stovall dining with his son.

GSE Dean José Luis Alvarado reads from Ecclesiastes.

“It was evident how close they were, just seeing them together. We chatted briefly, and we both went about our meals and while that was only a fleeting moment, it gave me insight into Tyler as a loving father that you simply can’t get unless you see it for yourself,” said Zapata. “While it was a serendipitous encounter with a friend and colleague at a local neighborhood restaurant, such experiences are what transformed mere physical spaces into places of community. He was also the kind of person you enjoyed running into.”

Auricchio agreed that the pandemic’s virtual environs paled in comparison to being in the same room with Stovall, albeit in many cases the colleagues met at the cold outdoor sheds that replaced restaurant dining rooms during the pandemic. Still, he never complained, even though he had just arrived from balmy California. Eventually, plenty of indoor meetings followed. There, Auricchio said, she found more than a groundbreaking scholar and able administrator.

“I found a dedicated and compassionate colleague driven by a commitment to social justice, antiracism, and true, true care for student well-being,” she said. “I found a thoughtful and inspiring interlocutor whose words were sometimes few, but always on the mark. And of course, I found a friend.”

Provost Dennis Jacobs offers words of gratitude.

His cousin said that in the weeks since Tyler’s passing, there has been “one constant theme” in the many tributes received by the family.

“It’s been some variation of, ‘Wow, I knew he was accomplished; I didn’t know he was this accomplished,” Smith said to the crowd of deans, faculty, and students after he and others spoke about Stovall’s accomplishments. “I’m sure many of you here were aware of what a giant Tyler was in his professional life, but on the chance that you didn’t know the depth and the character of his roots, hopefully now you do.”

Smith had told guests about Stovall’s grandfather, Otha Fuller, a hard-working West Virginia coal miner “who was known to preach the gospel on Sundays in church.” His “no-nonsense” wife, Pearl, made sure seven of their nine children went to college, including Stovall’s mother. As a college graduate herself, she inspired in her son a love of education.

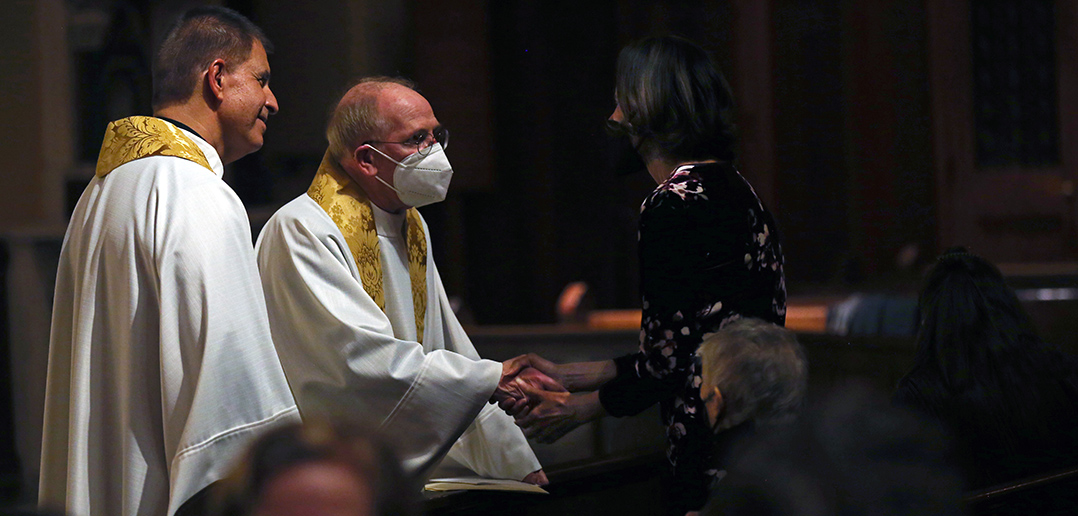

Vice President for Mission and Ministry John Cecero, S.J., and Father McShane greet Denise Herd.

“That is how Tyler Stovall made it to Fordham. That’s how his 12 other maternal cousins became doctors, lawyers, politicians, teachers, engineers, graphic artists, and broadcasters—by way of fine universities like Stanford, Harvard, Michigan,” he said.

Smith told of family lore that portrayed his grandparents as affectionately at odds. His said grandfather often dismissed his wife’s strong-willed declarations by saying (out of earshot) that he knew more of the world than she because he had been to Paris. Fuller was one of 400,000 Black soldiers fighting overseas in World War I.

“The man who loved to say I’ve been to Paris, France, had a grandson who became one of America’s foremost scholars on Paris, France. To me, that’s just perfect.”

Jack Smith holds up a copy of Stovall’s “Paris Noir,” which was dedicated to Stovall’s wife and his grandfather.