“Monsignor Shelley was a beloved and important member of the Fordham community. I was personally so grateful for his history of the University, which will forever help me continue the work of my predecessors,” said Tania Tetlow, president of Fordham. “My heart goes out to Father McShane and all of Monsignor Shelley’s family and friends.”

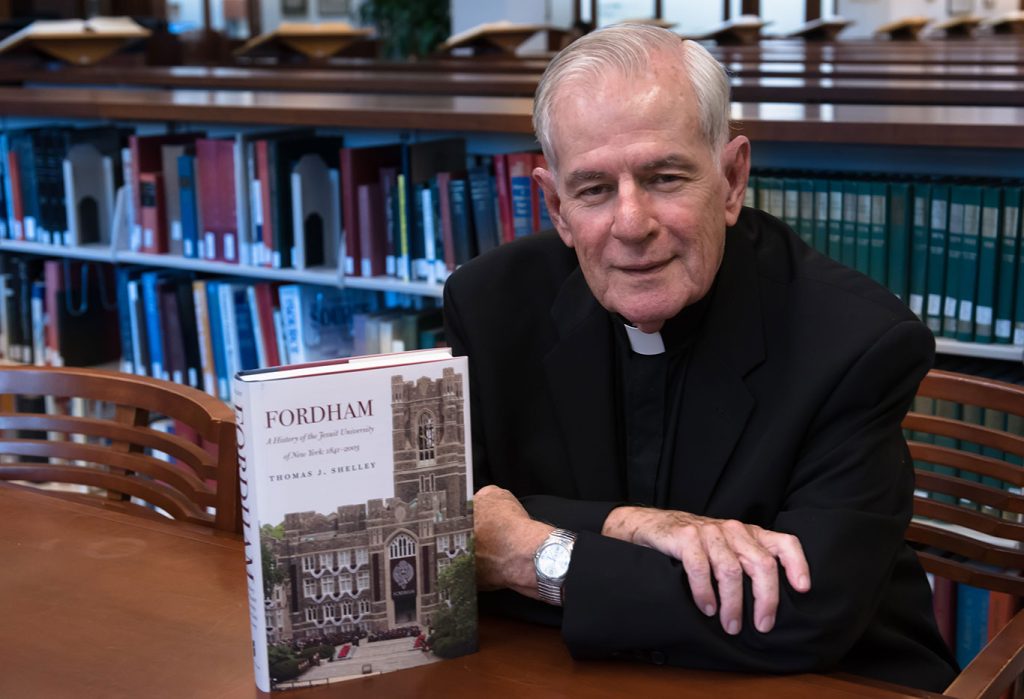

Monsignor Shelley’s role at Fordham went beyond his official title, thanks to the monumental task he took on in telling the University’s story. His book Fordham, A History of the Jesuit University of New York: 1841–2003 (Fordham University Press, 2016), is seen by many as the go-to source on matters of Fordham’s founding and first 175 years.

He was also a first cousin of Joseph M. McShane., S.J., president emeritus of Fordham, who called him a “master of tale and story” and a compassionate priest whose serious scholarship was balanced by an avuncular personality that endeared him to students, and a concern for the poor.

“You see in the history of the University, the history of the archdiocese, and in the parish histories he wrote, the people that he was most drawn to were people who were most authentic, who were true to mission, who watched out for the poor, were not flatterers, nor were they flattered,” he said.

“He was drawn to the hardworking people in the parishes, hardworking priests who didn’t spend a lot of time in the rectory but were out walking through the parish, seeing what was going on and so on.”

Although Monsignor Shelley was 12 years older than Father McShane and lived four miles away in the neighborhood of Melrose, he loomed large in the life of the McShane family. He was the first on the Shelley side of the family to attend college and was among the first to join “the family business,” said Father McShane, who stepped down as Fordham’s president in June.

When then-Deacon Shelley was assigned to Midnight Mass at Our Lady of Mount Carmel on a snowy Christmas Eve, Father McShane recalled, it was a big deal when he stayed the night across the street with his grandmother rather than return to the seminary.

“I can remember his ordination, I can remember his first Mass, and I can remember the dinner following his first Mass, which was at the Concourse Plaza Hotel,” he said.

“I also remember the menu at that dinner. So that will tell you something about the place he had in our family.”

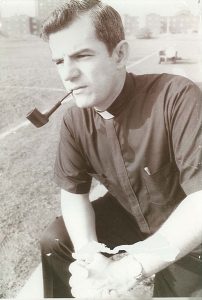

Thomas Joseph Shelley was born in 1937 to Thomas Shelley and Helen Walsh Shelley. He was the oldest of three children; his twin sisters Helen and Mary were born seven years later. He attended Cathedral College high school in Manhattan received a B.A. in philosophy in 1958 and an M.A. in theology in 1962 from St. Joseph’s Seminary and College, and was ordained a priest in 1962. He served as a parish priest for the Saint Thomas More Church, and after retiring, he served at Sunday Masses at Church of the Ascension, both in Manhattan. In 1966, he earned an M.A. in history from Fordham’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. He earned a doctorate in church history at Catholic University in 1987.

After 30 years of teaching history and religion at both the high school and seminary levels—including Stepinac High School, Cardinal Spellman High School, and Cathedral College—he joined Fordham’s theology department in 1996. He taught courses such as 19th-Century Catholicism, The Church in Controversy, and Faith and Critical Reason for 16 years, and in 2012, he retired, and was awarded the title of Professor Emeritus at Fordham.

He specialized in 19th- and 20th-century American Catholicism, particularly in New York City. In 1993, he published Dunwoodie: The history of St. Joseph’s Seminary, Yonkers, New York (Christian Classics), and in 2007, as a part of the Archdiocese of New York’s commemoration of its 200th anniversary, he was commissioned to write The Bicentennial History of the Archdiocese of New York: 1808-2008. (Editions Du Signe, 2007).

He was also a prolific contributor to America, which honored him with a tribute on Nov. 15.

In 2008, Father McShane asked him to write a history of the University from its founding to 2003, the year that Father McShane succeeded Joseph A. O’Hare, S.J. as president.

Father McShane said he knew from Monsignor Shelley’s prior work that he could trust him to do a “warts and all” exploration of the University.

“Tom took his work very seriously, he took his students very seriously, he took his colleagues very seriously. He took being a priest very seriously. The only thing he didn’t take seriously was himself,” he said.

Photo by Chris Taggart

Eight years later, Monsignor Shelley completed the 536-page history, complete with black and white and color photos, just in time for the University’s 175th-anniversary celebration. Among the conclusions he came to was that Fordham Founder Archbishop John Hughes “anticipated the work of the Second Vatican Council by a whole century.”

In 2016, he spoke to Fordham Magazine about taking on such a huge task.

“The Jesuits made my work easy because they carefully preserved so much of Fordham’s history in their archives, both here in New York City and also in Rome. Prior to 1907, Fordham (which was still called St. John’s College at the time) is the story of a small liberal arts college in the rural Bronx. After 1907, with the establishment of the first graduate schools (and the transition from college to university), the plot thickens. Each of the graduate schools has its own distinct identity and history, so the story becomes more complicated,” he said.

Monsignor Shelley was an active part of the 175th-anniversary celebration, delivering the homily at a Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and participating in a panel discussion about the University’s history. Although he himself was not a Jesuit, he attributed the University’s success, even through its roughest years, to the Society of Jesus.

Photo by Leo Sorel

“The popularity of Jesuit education for the last four centuries has been due in large measure to one factor: the fact that it’s rooted in the Christian humanism of the Renaissance and the positive aspects of the Catholic reformation,” he said.

Shelley continued to work on behalf of the University and the Church. In 2019, he published Upper West Side Catholics: Liberal Catholicism in a Conservative Archdiocese (Fordham University Press), and last April he delivered the homily at a Mass celebrating the opening of the Joseph M. McShane S.J. Campus Center. In June, at Father McShane’s request, he completed a final chapter of Fordham’s history that tackles Father McShane’s own time in office. Next spring, his book John Tracy Ellis: An American Catholic Reformer will be published by Catholic University Press.

Elizabeth Johnson, C.S.J., distinguished professor of theology, said Monsignor Shelley’s focus on “smart institutional history” was invaluable.

Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Johnson

In his history of the Archdiocese of New York, for example, Johnson noted that Monsignor Shelley dispelled the notion that the church was always associated with immigrants. In fact, in the years before the American Revolution, it was a church of the elite, dominated by figures such as Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron of Baltimore, an English nobleman who was the first proprietor of the Province of Maryland.

“He kept bringing up these sorts of discoveries and insights that would otherwise go untold. It wasn’t hagiography. It was very clear-eyed,” she said.

That volume also brought to mind one of Johnson’s favorite memories of Monsignor Shelley. While working in Fordham’s archives, he discovered correspondence between Archbishop Hughes and nuns working in Greenwich Village. They had been caring for non-Catholics, and Archbishop Hughes demanded they cease and desist. They informed him that after reading the Gospels, they concluded that Jesus would side with them, not him.

“He said, ‘What do you think?’ I said ‘Tom, this has to go into the book. And it did!’ Johnson said.

“He had the eye for what was really going on, and his deep allegiance was always to Christ and the gospels. I could see someone else writing a history of the Archdiocese who would just want to bury that.”

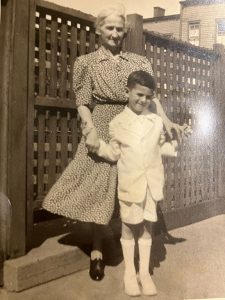

Photo courtesy of Mary Shelley

Christine Firer Hinze, Ph.D. chair of the theology department, said that it was beneficial to the theology department to have a diocesan priest on staff who taught seminarians, as he did at St. Joseph’s Seminary, where he was also named professor emeritus.

“He had his foot in both worlds, and that was incredibly helpful and enriching for us,” she said.

“The Archdiocese of New York is our home, but it can feel a little distant because of the stand-alone nature of a university.”

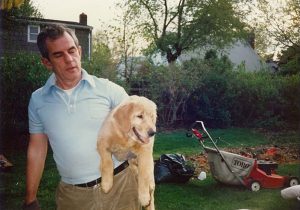

When the pandemic hit, Shelley moved back to the house in Long Island that his parents moved to in 1956, to be with his surviving sister, Mary Shelley. She said he was worried about her because of the Covid tally on Long Island and wanted to ensure she was not alone.

It was a blessing to have him back during that time, said Mary just after Monsignor Shelley died. She noted that as a night owl, he took full advantage of an open schedule, staying up until 3 a.m. to write his last book. He knew when he was an altar boy that he wanted to be a priest, she said. In June, he celebrated his 60th anniversary as a priest.

“His heart and soul, body and mind, were focused on the priesthood,” she said.

Photo courtesy of Mary Shelley

In addition to his being a lifelong Montreal Canadians fan and a lover of animals, Mary said she would always remember her brother for his compassion. When Helen died in 2013, he helped her with her grief, as he had many times before.

“We lost our parents very young, and I asked him why it hurts so much. He said ‘That’s the price you pay for love,’ and it’s true,” she said.

“He would help anyone, and he was honest. If things were bad, he would tell you. He was a composite of everything you’d want to have in a person.”

Father McShane said that several recent moments will stand out to him, including the many family funerals they were both called to serve at. At one point, Monsignor Shelley offered to take on the job of preaching, while letting Father McShane be the celebrant. It’s a more difficult job, but he offered to do it, because he had more time to write. On Friday, Father McShane will be the one at the pulpit, at his cousins’ funeral, and he said he’ll always be grateful for the way Monsignor Shelley helped him with the grief he felt at his mother’s funeral.

“When we were lining up for the procession, he walked by, patted me on the shoulder, and said, ‘You’ll be okay. You’ll be okay.’ And I looked at him and said, ‘Are you sure?’ He said, ‘I’m sure you’ll be just fine.’”

Photo by Chris Taggart

Shelley is survived by his sister Mary Shelley. He is preceded in death by his parents and his sister Helen.

A wake will be held Thursday, Nov 18, from 1 to 3 p.m. at the Main Chapel of the John Cardinal O’Connor Pavilion, 5655 Arlington Avenue, Riverdale, N.Y.

A funeral will be held at 10 a.m. on Friday, Nov. 18, at Church of the Ascension, 221 W 107th St. A wake will also be held in the church from 9 a.m. to 10 a.m. before the funeral.

Notes of condolences can be sent to Mary Shelley at 2408 Eighth Street, East Meadow, NY 11554.