With more than 50 countries holding national elections in 2024, information will be as important to protect as any other asset, according to cybersecurity experts.

And misinformation, they said, has the potential to do enormous damage.

“It’s a threat because what you’re trying to do is educate the citizenry about who would make the best leader for the future,” said Karen Greenberg, head of Fordham’s Center on National Security.

Greenberg, the author of Subtle Tools: The Dismantling of American Democracy from the War on Terror to Donald Trump (Princeton University Press, 2021), is currently co-editing the book Our Nation at Risk: Election Integrity as a National Security Issue, which will be published in July by NYU Press.

“You do want citizens to think there is a way to know what is real, and that’s the thing I think we’re struggling with,” she said.

At the International Conference on Cyber Security held at Fordham earlier this month, FBI Director Chris Wray and NSA Director General Paul Nakasone spoke about the possibility of misinformation leading to the chaos around the U.S. election in a fireside chat with NPR’s Mary Louise Kelly. But politics was also a theme in other ICCS sessions.

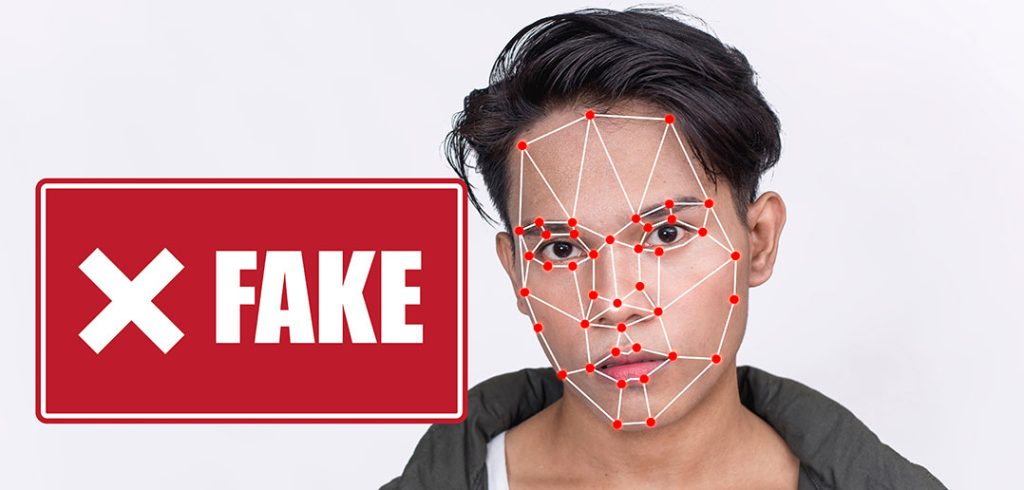

Anthony Ferrante, FCRH ‘01, GSAS ‘04, global head of cybersecurity for the management consulting firm FTI, predicted this year would be like no other, in part because of how easy artificial intelligence makes it to create false–but realistic—audio, video, and images, sometimes known as deepfakes.

Photo by Hector Martinez

The Deepfake Defense

“I think we should buckle up. I think we’re only seeing the tip of the iceberg, and that AI is going to change everything we do,” Ferrante said.

In another session, John Miller, chief law enforcement and intelligence analyst for CNN, said major news outlets are acutely aware of the danger of sharing deepfakes with viewers.

“We spend a lot of time on CNN getting some piece of dynamite with a fuse burning on it that’s really hot news, and we say, ‘Before we go with this, we really have to vet our way backward and make sure this is real,’” he said.

He noted that if former President Donald Trump were caught on tape bragging about sexually assaulting women, as he was in 2016, he would probably respond differently today.

“Rather than try to defend that statement as locker room talk, he would have simply said, ‘That’s the craziest thing anybody ever said; that’s a deepfake,” he said.

In fact, this month, political operative Roger Stone claimed this very defense when it was revealed that the F.B.I. is investigating remarks he made calling for the deaths of two Democratic lawmakers. And on Monday, it was reported that days before they would vote in their presidential primary elections, voters in New Hampshire received robocall messages in a voice that was most likely artificially generated to impersonate President Biden’s, urging them not to vote in the election.

A Reason for Hope

In spite of this, Greenberg is optimistic that forensic tools will continue to be developed that can weed out fakes, and that they contribute to people’s trust in their news sources.

“We have a lot of incredibly sophisticated people in the United States and elsewhere who understand the risks and know how to work together, and the ways in which the public sector and private sector have been able to share best practices give me hope,” she said.

“I’m hopeful we’re moving toward a conversation in which we can understand the threat and appreciate the ways in which we are protected.”