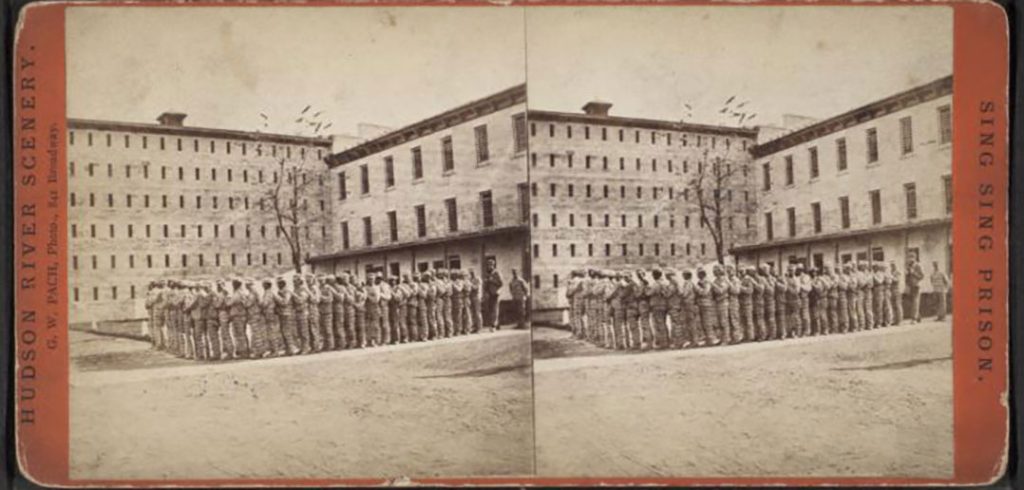

From 1865 to 1925, nearly 50,000 people passed through the gates of Sing Sing prison, just 20 miles north of New York City.

Very little is known about who they were.

Shadows on Stone, a new crowd-sourced digital history project that began in a Fordham history class, seeks to fill in that gap and, in doing so, help restore the humanity of a group of people who have historically been dismissed as irredeemable.

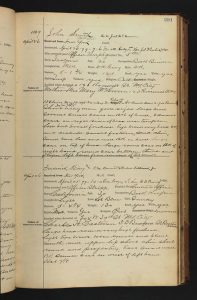

The goal of the project is to transfer digitized records that were entered when prisoners first arrived at the prison. Since only a very small number of the inmates ever wrote about their time there, these “mini-biographies” of their lives before imprisonment offer the only glimpses of who they were.

Anyone who would like to help is welcome to try their hand at transforming the hand-written documents into legible text that will eventually be entered into a searchable database.

Analyzing Data in a Fordham History Class

The project first began in 2018, when Fordham undergraduate students in two honors history classes were tasked by now-retired professor Roger Panetta, Ph.D., to analyze some of the entries from the first set of names. The data was then uploaded to the crowd-sourcing research site Zooniverse.

The students published two reports based on their findings: The NYC Criminal and Sing Sing Penitentiary in the 19th Century and Paved with Good Intentions: Origins of the New York Penitentiary. They also created an entry that is currently on the Sing Sing Museum’s webpage.

Open to Public Volunteers

Panetta, who is writing a book about Sing Sing, decided to expand the project and open it to the public. A soft launch for the Shadows on Stone took place in August; it will fully go live in October.

Anyone who would like to help is welcome to try their hand at transforming the hand-written documents into legible text that will eventually be entered into a searchable database.

Panetta said the data on these inmates was originally collected as part of a movement in the 19th century to identify the so-called “criminal class.”

Using ‘Fragmented Biographies’ to Gain Insight

“When I first saw the records, I thought, ‘Oh, this is great stuff.’ So-and-so grew up here, lived on this street, committed this crime, had no parents. Or, one parent was a Catholic, one spoke Italian, one could read, one could not read, one had these scars on his body, and so on,” he said.

“I began to wonder if these would constitute a kind of fragmented biography, which could give us an insight into who they were. We could then begin to challenge the popular view that they’re just bad, horrific people.”

In 2015, the State of New York let Ancestry.com scan all the logbooks containing these records and make them publicly viewable. They’re still handwritten, though, so it’s fallen to volunteers to decipher the handwriting and record it digitally for further analysis.

For those who have trouble reading the handwriting, there are tools allowing users to zoom in on the entry as well as a forum for discussing them.

Influencing Conversations on Mass Incarceration

In time, Panetta said he hopes that understanding the past of a place as legendary as Sing Sing can influence current conversations around incarceration in the United States.

“The contemporary view of victims of mass incarceration is they’re Black, they’re poor, they’re undereducated,” he said, adding that there’s much more at play and even characteristics like dyslexia can play a role.

“[Mass incarceration] is a problem. We think it has to do with race. We think it has to do with economic conditions. We know it has to do with educational levels. And so the thinking is, ‘Maybe we should look more closely.’ That can help us break the cycle of incarceration.”