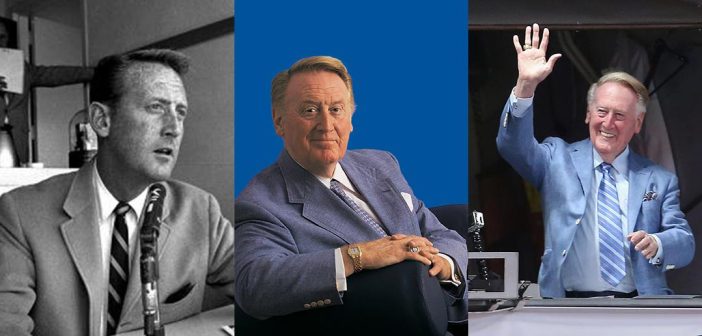

It was a voice he honed as an undergraduate at Fordham, where he majored in communications and was one of the original staff members of WFUV, Fordham’s public media station. During a major league career spanning 67 seasons—from 1950, when he joined the Dodgers, to 2016—he described some of the most memorable moments in baseball with poetic simplicity and exquisite timing.

He had an uncanny ability to frame the drama as it unfolded—and he was known for the wisdom, humor, and humility he conveyed to people, on and off the air.

Here are some of his most memorable calls and heartfelt words of gratitude and wisdom.

Don Larsen’s Perfect Game: ‘The greatest game ever pitched’

On October 8, 1956, the defending champion Brooklyn Dodgers faced their Bronx rivals, the New York Yankees, in the fifth game of the World Series.

Scully split the TV broadcasting duties that day with Yankees announcer Mel Allen, who kidded his colleague in the top of the second inning when a foul ball zipped by the broadcast booth. “Vin Scully played baseball at Fordham, but even so, he flinched just a little on that one,” Allen said. “Forgot to bring his glove with him today.”

Scully may not have had his glove in the booth, but he certainly had poise and a bit of poetry. He took over from Allen in the bottom of the fifth and guided fans to the game’s final, dramatic out, when Yankees pitcher Don Larsen completed a perfect game—retiring all 27 Dodgers he faced. It’s a feat no pitcher had done before and no pitcher has done since in the World Series.

As the final batter stepped to the plate, Scully conveyed the sense of nervous anticipation throughout the ballpark: “Yankee Stadium,” he said, “shivering in its concrete foundation now.” And when Larsen struck out Dale Mitchell to end the game, Scully said simply, “Got him! The greatest game ever pitched in baseball history, by Don Larsen. A no-hitter, a perfect game, in a World Series.”

Sandy Koufax’s Perfect Game: ‘29,000 people … and a million butterflies’

Nearly a decade later, on September 9, 1965, Scully was behind the mic for another perfect game, this one by the Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax, who had already pitched three no-hitters in his illustrious career. The game was not televised, however, so Scully’s evocative call of the final half-inning helped listeners see and feel the drama.

“And you can almost taste the pressure now,” he said after the second strike against the inning’s leadoff hitter, Chris Krug. “Koufax lifted his cap, ran his fingers through his black hair, then pulled the cap back down, fussing at the bill. Krug must feel it too as he backs out, heaves a sigh, took off his helmet, put it back on, and steps back up to the plate.”

Moments later, Scully said, “And there are 29,000 people in the ballpark and a million butterflies.” And in the middle of the inning, he made this poignant observation: “I would think that the mound at Dodger Stadium right now is the loneliest place in the world.” Listen to the entire ninth inning:

Hank Aaron’s 715th Home Run: ‘What a marvelous moment for the country and the world’

On April 8, 1974, the Dodgers traveled to Atlanta to play the Braves, whose veteran slugger, Hank Aaron, was one home run away from breaking Babe Ruth’s record of 714 career home runs. In the fourth inning, Aaron stepped up to the plate with Scully behind the mic to describe a drama that would resonate far beyond the ballpark.

“It’s a high drive into deep left-center field. Buckner goes back to the fence. It is gone!” Scully said, then let the crowd take the mic for 26 jubilant seconds before remarking on Aaron’s historic achievement: “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

1982 NFC Championship Game: ‘It’s a madhouse at Candlestick’

Scully was best known as a baseball broadcaster, but he also covered golf and football for CBS, and on January 10, 1982, he called one of the most memorable games in NFL history. In the final minute of the NFC championship game at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, the Dallas Cowboys led the hometown 49ers 27-21. With the ball on the Dallas six-yard line and a trip to the Super Bowl at stake, San Francisco quarterback Joe Montana took the snap and rolled right. “Montana looking, looking, throwing in the end zone,” Scully said. “Dwight caught it! Dwight Clark!” Scully let the crowd roar for nearly 30 seconds before returning to the mic: “It’s a madhouse at Candlestick, with 51 seconds left,” he said. “Dwight Clark is six, four; he stands about 10 feet tall in this crowd’s estimation.” Watch the clip and listen to Scully’s call.

National Baseball Hall of Fame: ‘I want to sing, I want to dance’

On August 1, 1982, Scully received the highest honor a baseball broadcaster could receive—the Ford C. Frick Award, presented annually by the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, to honor a broadcaster for “major contributions to baseball.”

He was 54 years old at the time and not quite at the halfway mark of his career, as it turned out. He still had 34 seasons ahead of him—and numerous honors, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which he received from President Barack Obama in 2016.

His acceptance speech in Cooperstown, with his wife, Sandi, and children looking on, is a prime example of his humility and gratitude. “Why, with the millions and millions of more deserving people, would a red-haired kid with a hole in his pants and his shirttail hangin’ out, playing stickball in the streets of New York, wind up in Cooperstown? Why me indeed?”

He didn’t have an answer, he said, but “I do know how I feel: I want to sing, I want to dance, I want to laugh, I want to shout, I want to cry. And I’d like to pray. I’d like to pray with humility and great thanksgiving.”

Game 6 of the 1986 World Series: ‘If one picture is worth a thousand words, you have seen about a million words’

On October 25, 1986, Scully was at Shea Stadium in Queens, where the New York Mets hosted the Boston Red Sox in Game 6 of the World Series. The Red Sox were up two runs and only one out away from ending the Mets season and breaking the so-called Curse of the Bambino—at that time, the Red Sox had not won a World Series since trading Babe Ruth to the Yankees after the 1919 season.

With their season on the line, the Mets staged a gritty two-out comeback to tie the game in the bottom of the 10th inning. And then, after fouling off pitch after pitch, the Mets’ Mookie Wilson finally hit a seemingly routine ground ball toward first baseman Bill Buckner.

“Little roller up along first, behind the bag, it gets through Buckner!” Scully said, his voice rising. “Here comes Knight, and the Mets win it!” Once again, he let the crowd roar—this time for nearly two minutes, as viewers were shown the replay of Buckner’s error, a delirious New York crowd, the jubilant Mets, and the despondent Red Sox. “If one picture is worth a thousand words,” Scully said when he returned to the mic, “you have seen about a million.”

Kirk Gibson’s Walk-Off Home Run: ‘In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened’

On October 15, 1988, Scully was in the booth at Dodger Stadium to call the opening game of the World Series. The Oakland A’s led the Dodgers 4-3 with two outs in the ninth inning and their star reliever, Dennis Eckersley, on the mound. When injured Dodgers star Kirk Gibson emerged from the dugout to pinch hit with the tying run on first base, Scully set the stage masterfully.

“All year long, they looked to him to light the fire, and all year long, he answered the demands—until he was physically unable to start tonight, with two bad legs: the bad left hamstring and the swollen right knee. And with two out, you talk about a roll of the dice, this is it.”

Gibson gamely fouled off several pitches and worked the count to 3-2 before connecting on a backdoor slider. “High fly ball into right field, she is gone!” Scully said, as Gibson hobbled around the bases. Scully then let the crowd roar for 67 seconds before adding: “In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened.”

Fordham Commencement: ‘It’s only me, and I am one of you’

On May 20, 2000, Scully received an honorary degree from Fordham and delivered the commencement address. “It’s only me, and I am one of you,” he told the Class of 2000. “I walked the halls you walked. I sat in the same classrooms. I took the same notes and sweated out the final exams; drank coffee in the caf and played sports on your grassy fields.”

“This world … will try very hard to clutter your lives and your minds,” he told them. “Leave some pauses and some gaps in your life so that you can do something spontaneously rather than just being led by the arm. And, above all, dream. Don’t ever stop dreaming. Dream for yourselves and dream for us, because out of your dreams will come hope that we will have a better world and a better moral climate.”

Final Innings: ‘Smile because it happened’

On October 2, 2016, Scully called his final game: a contest between the Dodgers and the Giants in San Francisco. He told a story about Giants announcer Russ Hodges’ famous call of the 1951 pennant-winning home run by Bobby Thomson. Willie Mays joined him in the booth at one point, and so did many members of his family, including 16 grandchildren, three great-grandchildren, and his wife, Sandi. “What a way to celebrate your last game,” he said, “having your family here with you.”

In the final inning, Scully said that he’d had a line in his head all year, a common, anonymous expression often mistakenly attributed to Dr. Seuss, he said. “The line is, ‘Don’t be sad that it’s over. Smile because it happened.’ And that’s really the way I feel about this remarkable opportunity I was given, and I was allowed to keep for all these years. … I have said enough for a lifetime, and for the last time, I wish you all a very pleasant good afternoon.”