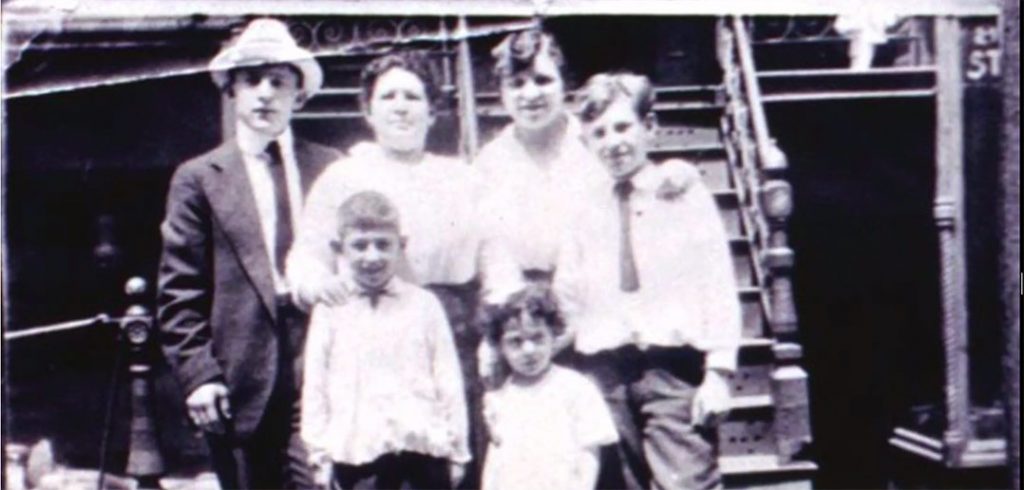

They were immigrants building a new life and a new identity as Americans in New York City in the early 20th century. Their building is now part of the Tenement Museum, which highlights the stories and contributions of immigrants like those who once filled the austere tenement buildings on the Lower East Side.

On Sept. 22, the staff gave a virtual tour organized by Fordham’s Office of Alumni Relations, focusing on the Rogarshevsky family, Lithuanian Jews who came to America in 1901 and lived in one of two tenement buildings now maintained by the museum.

“We work to tell very specific stories, because we find that that is easier to identify with,” said Danielle Wetmore, a lead educator at the museum. “None of us live our lives in statistics.”

The sold-out event drew approximately 50 people from 14 states as well as Brazil.

Envisioning the Past

The Rogarshevskys came to America seeking economic opportunity, said Wetmore, noting that anti-Semitic laws may have made it harder for them to find that in their home country.

To help with imagining what the Rogarshevskys’ immigrant experience may have been like, the tour included period images such a crowded city street that would be a striking change from the family’s more rural home. “It’s going to be loud. … They’ve never seen so many people,” Wetmore said.

Other pictures showed their restored apartment in the museum’s building at 97 Orchard Street, with its window separating two rooms to promote ventilation and ward off a scary virus of that era, the one causing tuberculosis. (The family’s father, Abraham, would die of the disease.)

There was no ice box, so the mother, Fanny, would have gone grocery shopping every day. The building had no showers, so a deep clean would have required a trip to a neighborhood bathhouse—2 cents for five minutes. “That is done maybe once a week, maybe a little less than once a week,” Wetmore said. Families typically spent about half their income on rent, she said.

Were their living conditions a step up? Hard to say—“It’s always going to be a mix” of better and worse, compared with the home country, Wetmore said. “The way your space feels is different. The kind of compromises you’re making here regarding space are different than you made in Lithuania.”

Within the diversity of the city, there could be clusters of immigrants from the same part of the world, as earlier immigrants helped family members and former neighbors make the trip, said one of the presenters, Fordham history professor Daniel Soyer, Ph.D. “Sometimes you can look at the census and you’ll find that [even in]a building, there will be a bunch of different families from the same place,” said Soyer, author and coauthor of several books including Jewish New York: The Remarkable Story of a City and a People (NYU Press, 2017).

A New Language

Wetmore noted the tension between speaking one’s native language—in this case, Yiddish—versus stepping into a new, American identity by speaking English. Soyer said Yiddish had lower social status and younger people wanted to speak English; they learned it in the public schools, although with varying retention, while at least remembering their linguistic heritage.

“[For] the rest of their lives, they may understand every word when someone speaks Yiddish but not be able to speak it themselves,” he said.

A popular form of entertainment was dime novels, some of them formulaic romances featuring a downtrodden heroine who winds up in love and married at the end, Wetmore said. At the time, arranged marriages were on the decline, and the Rogarshevskys’ two daughters, Ida and Bessie, may have dreamed about falling in love, she said.

“Abraham did not like his daughters to read romance novels,” Wetmore said. But Ida and Besse liked them. And they were written in English, which Abraham couldn’t read, so he wouldn’t have known if they were obeying him, she noted.

Social Unrest

Labor issues of the day may have come up at home, Wetmore said. There were calls for strikes to address poor working conditions in factories, where workers had to put in 70 hours a week and risked losing an entire week’s pay for making one mistake or being fired if they made three, she said.

This activism grew more urgent in 1911 after a fire in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory—the top three floors of a nearby Greenwich Village building—claimed the lives of 146 workers who couldn’t escape via doors, the elevator, or the fire escapes, which weren’t made to be weight bearing. The majority of the dead were young immigrant women like Ida and Bessie, who worked in factories themselves.

The deaths fueled conversations about bringing change. “This conversation makes me curious how the [Rogarshevsky] parents’ views of union membership or striking or solidarity maybe change because of this tragedy,” Wetmore said.

A Journey in Name

The family changed its name from Heller, in Lithuania, to Rogarshevsky in New York and later to Rosenthal. Soyer noted that last names were “very slippery things” in Eastern Europe, especially among Jews, who “may not have had much attachment to them” because they had been made to take them in the 19th century.

And, he added, “it’s a complete myth that people changed their names at Ellis Island.”

“Most Jewish name changes in New York took place much later than people think,” he said. “It was really in the second generation, as people were upwardly mobile.”

The Zoom session’s chat screen was a churn of comments throughout the 90-minute event as people asked about the family’s story and related their own experiences to it. And that was the point of the event—“What does [the Rogarshevskys’ story]tell us about the story of immigrants today,” Wetmore said, “and how does this story then impact our views or our relationships with immigration and immigrants in our modern world?”

The virtual tour of the Tenement Museum was one of many cultural events held regularly by the Office of Alumni Relations.