Bill Breisky recalls his grandfather Victor Hess, who discovered cosmic radiation 100 years ago and spent more than a quarter-century teaching physics and conducting research at Fordham.

Victor Francis Hess and I inhabited different worlds. He was born in the green heart of Austria and schooled in physics and mathematics in its Renaissance capital, Graz. I was born in the smoky city of Pittsburgh and schooled in the very unscientific world of journalism.

And yet, we shared common ground. Both of us loved searching for truth and unraveling mysteries (we shared a passion for Eric Ambler spy novels), and of course we loved Grandma Hess and her incomparable dumplings and strudels. She had married Victor two years after her first husband, Artur Breisky, a retired major in the Austro-Hungarian army, died during the First World War.

I first set eyes on my Austrian grandparents in Innsbruck in mid-1932, in the heart of the Great Depression. The Hesses had offered to share their apartment there after my father lost his job in Pittsburgh and suffered a nervous breakdown. I was almost 4 years old at the time, and my brother Arthur was an infant. His howling became an issue for grandma—or “Ma-ma,” as she was called. She demanded peace and quiet so that her husband the professor, my step-grandfather, could concentrate on his papers and have an afternoon nap.

It was a tumultuous year for both families, with young Nazis, the Heimwehr, and Bolsheviks clashing in the streets “right outside our window,” my mother reported in a letter home. But there were many good times, one of them a visit to the new cosmic radiation observatory Victor Hess had established one year earlier on Mount Hafelekar, outside of Innsbruck. My mother wrote in the Hafelekar guest book: “The top of the morning, and the top of the world!” She signed it, “Laura Breisky and Billy, Pittsburgh, Pa., U.S.A.”

Two years later, back in Pittsburgh, Laura Baer Breisky died of breast cancer.

We were still in Pittsburgh in 1936 when we received a telegram from Innsbruck informing us that Victor Hess was, belatedly, to be awarded a Nobel Prize in physics for his discovery of cosmic radiation during the daring experiments he had conducted while aloft in a balloon more than two decades earlier. To celebrate, the Hesses sent my brother and me garments that were a source of amusement at the Pittsburgh school I attended—lederhosen.

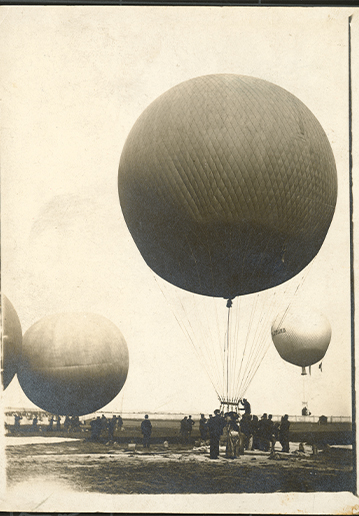

Scientific Explorer: From 1911 to 1913, Victor Hess took to the skies in a series of daring hot-air balloon flights to demonstrate the existence of cosmic radiation.

By 1938, we had moved to Baltimore, and Hitler had moved into Austria. Fascist-dominated Europe was already in the midst of a great intellectual and cultural migration to America—Einstein, Pauli, Fermi, Stravinsky, Chagall—but the Anschluss hastened the process, and Austrians became the second largest national group in that migration. One writer called these emigrants “Hitler’s gift to America.”

Victor Hess, thanks to the Nazis—who dominated the faculty at the University of Graz—was made virtually penniless when he fled with my grandmother to Switzerland, having been forced to leave behind the Swedish crowns that had come with his Nobel award. The Nazis had declared grandma to be Jewish (she had converted to Catholicism but was irreligious) and grandpa to be “too cosmopolitan” (he had served as a science representative in Austria’s democratic government). But news of his plight spread rapidly, and he soon received the offer of a full professorship from Fordham University.

The Hesses spent Christmas with us in Baltimore that year, and I began a bond with my grandfather—one that lasted until his death, 26 Christmases later.

In 1943, I contracted double pneumonia, was hospitalized for eight weeks (penicillin had not yet been discovered), and recuperated with the Hesses for the summer at their apartment on William Street, in the Fleetwood section of Mount Vernon, New York. I had received the last rites of the Anglican church while in the hospital, and that prompted grandpa to tell me of his deep religious faith, and of the vow he had made after larynx-cancer surgery had left him with a voice that never rose above a hoarse whisper. He said he had vowed that if he were spared, he would attend Mass faithfully for the remainder of his life. He kept that vow.

“A scientist, more than other scholars,” he wrote during his first decade in America, “spends his time observing nature. It is his task to help unravel the mysteries of nature. He comes to marvel at these mysteries. Hence it is not hard for a scientist to admire the greatness of the Creator of nature. From this it is only a step to adore God.”

He took me to Mass on several Sundays after that. And to a movie, preferably one featuring Humphrey Bogart or James Cagney, on afternoons when he drove grandma to one of her bridge games. Grandpa and I cheered for the Yankees at Yankee Stadium, and we marveled at Pancho Segura’s two-handed swing in the Davis Cup tennis tournament. I learned that Victor Hess had been an avid tennis player as a young man.

I never saw my grandfather in tennis shorts, however. His day-to-day uniform was a three-piece Witty Brothers suit—or at least shirt, suspenders, trousers, and a vest. He required a vest with pockets ample enough to hold his gold pocket watch and chain, a packet of Chiclets chewing gum, a pen, and a small notebook, where a meticulous record of his expenses was recorded in a daily diary.

Victor Hess’ intellectual home in America was, of course, at Fordham—his laboratory, office, and lecture hall. One corner of his spacious office seemed reserved for instrumentation, to monitor the weather and measure breath samples with his good friend and colleague William McNiff, Ph.D. He and Professor McNiff developed a method of measuring small amounts of radium in the human body.

When I visited grandpa at Fordham as a boy, we would share lunch on a campus bench or at a Fordham Road restaurant that served an excellent fillet of sole for 40 cents. Those lunches often were followed by an afternoon of taking measurements—at times on a Harlem River pier where we tossed bits of raw sodium into the river and laughed at their explosive sizzle. He took me to the Empire State Building, where he and a colleague had taken measurements of radioactive fallout after Hiroshima. (He was appalled at the idea of nuclear testing after the war.) And a couple of times, I accompanied him to the 190th Street subway station beneath Fort Tryon, where he had obtained permission from the city to measure radiation in a granite wall some 400 feet below the surface.

I sat in on what I believe was his final lecture on the Rose Hill campus. He told his students that he had loved every class he had taught at Fordham.

Last year, I located one of his prize doctoral students from that time, Joseph Braddock, Ph.D., GSAS ’59. Braddock and two other physicists who studied under Hess while earning their doctorates left Fordham in 1959 to create the defense and technology contracting firm of Braddock, Dunn and McDonald, which went on to play a major role in the development of American anti-missile technology.

“My strongest memory of him is as a great lecturer—and a great listener,” Braddock said. “Often Bernie Dunn, Doctor Hess, and I sat down and had lunch, in the office or in the lab, and talked, frequently about opera. The unofficial Victor Hess was very warm.”

Grandma Hess died of cancer in 1955, at home, where she had been nursed lovingly by Elizabeth Hoencke, a German refugee. Before she passed away, grandma gave one final instruction to Victor: “Marry Elizabeth.”

Several months later, Victor did as he had been told. Elizabeth called her bridegroom “mein Schatz.” She accompanied him to Rome, when he was inducted into the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and to the White House to attend a dinner for Nobel laureates hosted by Jack and Jackie Kennedy.

Late in 1964, Victor was confined to a hospital bed in his living room. A week before Christmas, Elizabeth called our home in Connecticut to tell me, through her tears, that Parkinson’s and pneumonia had finally prevailed, and that her Victor had died.

Grandpa’s funeral, in Mount Vernon, was very small. I recall that a few Fordham Jesuits were there, along with Elizabeth’s family, but not many others. He seemed virtually forgotten, and that pained me. Grandpa Hess was buried in White Plains and gone from our lives, except in my memory.

Or so I thought.

In the fall of 2007, I underwent a procedure called proton-beam stereotactic radiosurgery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. A neurosurgeon targeted my cerebellum with high-energy protons that halted the growth of a benign tumor. Afterward, I asked the medical physicist who had worked alongside the neurosurgeon whether she had ever heard of a physicist named Victor Hess.

“Of course,” she replied, stunning with me with the news (it was news to me) that an observatory called H.E.S.S., or High Energy Stereoscopic System, had been established in Namibia to search the skies for the origin of cosmic rays. Another physicist at the hospital told me that the development of the particle accelerators that had made my radiosurgery possible was stimulated in large part by my grandfather’s balloon-flight discoveries.

In 2009, Grandpa Hess came alive for me yet again when my wife, my brother, and I visited the University of Vienna. I sat at grandpa’s old roll-top desk and examined the instrumentation he had devised for his historic 1912 balloon flights. And we met Professor Peter Schuster, who had been instrumental in establishing the Victor Franz Hess Society—in order, as he put it, “to bring him home to Austria, from which the Nazi regime had banished him, and to be once again the figurehead of Austrian physics we have been missing for too long.”

To my son John and my teenage grandson Ethan McPherson, Victor Francis Hess was a family legend and the subject of a gray photograph that hangs in my study—a stout, young mustachioed man in a three-piece suit, standing in the basket of a hot-air balloon. It seemed high time that they got to know Grandpa Hess better, so in the last week of May 2011, we paid our respects to the Rose Hill campus.

Our first stop was Freeman Hall. The Hess lab was gone, but there were countless reminders of him in the office of physics Professor Martin Sanzari, Ph.D., head of Fordham’s new engineering physics program. Sanzari had organized Victor Francis Hess Day earlier this year. We chuckled at a photo of an exuberant student wearing a T-shirt proclaiming, “Victor Hess Day is the Bess Day!” And we paused reflectively in Freeman’s lecture hall—so unchanged that I imagined I could find the seat I occupied on the last day that Victor Hess formally addressed his students.

The Arthur Avenue restaurant where we had lunch was recommended by none other than Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, who had warmly welcomed us into his office in late morning. Father McShane saw to it that John, Ethan, and I were outfitted with maroon Fordham caps before ushering us to the Administration Building’s Hall of Honor, where a Victor Hess plaque shares wall space with none other than Bronx-born baseball legend Frankie (“The Fordham Flash”) Frisch. Father McShane’s parting words to Ethan: “I’ll see you in four years.”

It was in the archives of Fordham’s William D. Walsh Family Library that the spirit of Victor Hess seemed most alive. In its stacks were copies of some of his letters to old colleagues who had made their way out of Nazi-occupied Europe to the United States—Swiss biologist Eugster on 54th Street in Manhattan, Austrian Nobel laureate Loewi on 93rd, Austrian ex-Chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg in St. Louis, among others.

We found a 1950 paper written by Hess the motoring adventurer on “The Capacity of a Highway.” (A maximum number of vehicles can travel safely and efficiently on a highway, he calculated, if they maintain a speed of 15 miles per hour.) And an astonishing discovery—the tattered address book he had kept atop his desk in Fleetwood containing the addresses of physicist Georg von Hevesy, his old balloonist companion; of Fordham colleagues McNiff, Weber, and Kovach; and, to be sure, those of prize students Braddock, Dunn, and McDonald.

Grandpa Hess would be surprised to learn that records of his work occupy 34 cubic feet in Fordham’s archives. He also would be surprised to find more women than men walking the Rose Hill campus. And I’m guessing that he would be pleasantly surprised that solar panels and a wind turbine are planned for the roof of Freeman Hall—while, as my son John the architect observed, the green and leafy Gothic-style campus appears virtually changeless, despite all its well-concealed modernization. A place of faith and reason, and beauty.

Ethan, who’s in ninth grade (my age in the middle of my Fordham-visiting years) googled Victor Francis Hess when he got home and promptly advised us, “He died on December 17. That’s my birthday!” Should I have been surprised? Grandpa Hess lives on.

The Latin inscription on the back of Hess’ Nobel medal, loosely translated, reads: “And they who bettered life on earth by their newly found mastery.”

Next August, Victor Hess will be remembered throughout the world as the scientific explorer who, 100 years earlier, made a series of historic flights—in what essentially was a flying basket—to demonstrate the existence of cosmic radiation. He will be remembered for his enduring love of nature, for his exploration of nature, and for his love of the Creator of nature.

He will also be remembered, by me, as the person who signed his letters, “Your loving Grandpa.”

—Bill Breisky is a former associate editor of The Saturday Evening Post. From 1978 to 1995, he was the editor of the Cape Cod Times.