Horbatiuk, an attorney who majored in history at Fordham College at Lincoln Center before earning a J.D. at Fordham Law School, has been enthralled by the storied bivalve since reading Mark Kurlansky’s 2006 book The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell. In public talks, he recounts oysters’ emergence as New York City’s leading export in the 19th century, when “New York had street cart vendors selling oysters for a penny a shell.” He also describes the demise of the city’s oyster beds due to overharvesting and pollution.

The Environmental Benefits of Oyster Restoration

In recent years, New Yorkers like Horbatiuk have been reintroducing oysters, not to be eaten but for the environmental benefits—the mollusk’s circulatory system filters contaminants from the city’s waterways, and the reefs help create habitats for other marine life. On Saturday mornings from May through September, he travels to City Island to measure the oysters’ growth, determine how many of them are growing on each craggy shell pulled from Long Island Sound, and pal around with a diverse group of volunteers devoted to the research project.

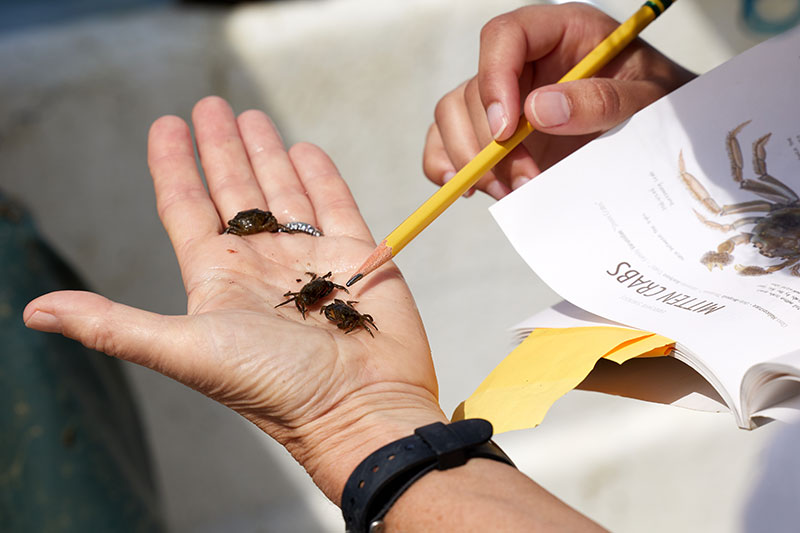

Measuring and counting the oysters is painstaking work that demands focus and dedication. Horbatiuk clearly has both, as he works methodically through an orange plastic pail filled with oysters affectionally labeled “Kevin’s Bucket.” His volunteer efforts that sunny Saturday morning in August were part of City Island Oyster Reef’s research study on oyster propagation and biodiversity in Long Island Sound. Among the species found living with the oysters that morning were grass shrimp, bristle worms, skillet fish, slipper snails, and boring sponges.

Horbatiuk recalls that in the 1830s, as many as 39 million bushels of oysters were harvested annually, with New York the center of the world’s oyster trade. Since industrialization, however, the oyster beds died. And today’s oysters, while helping to improve water quality by filtering up to 50 gallons of sea water a day, are inedible because the toxins that get filtered out remain in the oyster flesh.

“The history grabbed me first,” said Horbatiuk, who grew up on New York’s Lower East Side and now lives in the Riverdale section of the Bronx. “Very few people realize how important they are historically and what they do for the water’s health.”

‘Oysters for a Penny a Shell’

Horbatiuk’s love of the city’s past dates back to his undergraduate days at the Lincoln Center campus. His favorite courses focused on social and intellectual history, which helped illuminate developments in pop culture in American society.

His Saturday morning efforts on City Island dovetail with his role as a volunteer as an ambassador for the Billion Oyster Project, which does public outreach on oyster restoration and monitors oyster propagation in New York waterways. That outreach includes talks he gives throughout the metropolitan area to New Yorkers interested in learning more about the history of oysters. At his talks, he’ll mention that the Fanny Farmer cookbook from the 1860s had 40 recipes for oyster dishes. He’ll also hearken back to the early 1600s, when the Lenape people, who had lived in the region for centuries, traded oysters with the Dutch and piled them high in middens along the coast.

“It’s an easy sell to the public,” he says. “It just captures their imagination when you tell them you could find oysters in Spuyten Duyvil in the Bronx, and instead of hot dog carts on the street, New York had street cart vendors selling oysters for a penny a shell.”

In June, he manned a table at the New York Philharmonic performance at Lincoln Center that featured three classical pieces inspired by water—one depicted foreboding ocean moods and a vicious storm, while another portrayed the role of water in an Australian myth. During intermission, he chatted with concertgoers about the oyster project.

In mid-July, he participated in the City of Water Day by visiting the Sebago Canoe Club in Jamaica Bay in Brooklyn to talk about conservation and oyster restoration. That same month he spoke at the Beczak Environmental Education Center in Yonkers about the history of oysters in the Hudson River estuary. That’s where he’s a member of the Yonkers Paddling and Rowing Club and served as club commodore from 2019 to 2021.

“Kevin may be a lawyer, but he’s found another passion: the history of oysters,” said Bob Walters, executive director of the Beczak Center. “He tells that story with such enthusiasm and passion. And he’ll share what he’s learned at the drop of a hat.”