“I was always really interested in migration and movement—why people move and what happens when they move and how they form community,” said Maddox, an associate professor in the African & African-American Studies department.

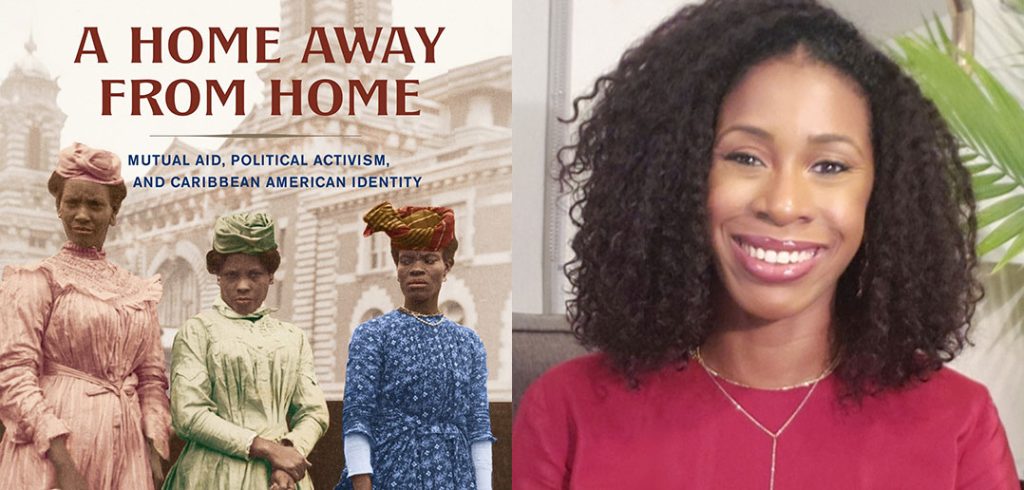

In her new book, A Home Away from Home: Mutual Aid, Political Activism, and Caribbean American Identity (University of Pennsylvania Press), Maddox explores those ideas, as well as the influence of organizations that supported Caribbean immigrants as they arrived in the U.S. around the early 1900s.

How did you come up with the idea for A Home Away from Home?

I knew that I wanted to work on some aspect of immigration or migration history for my Ph.D. [which she earned in 2016]. I started going to the Schomburg Center [for Research in Black Culture]in Harlem, and I found these records of Caribbean-American mutual aid societies. There were so many of them. I thought, “They’re really important. We should be talking about this.”

What did you learn from studying these mutual aid societies?

I realized that the societies were important for lots of reasons: helping migrants form community with each other and taking care of them in a time where there weren’t many outlets for Black immigrants.This is when we have a lot of segregationist laws in the U.S. toward Black people … and they’re not OK with that. They become really politically active. They’re fighting against anti-lynching laws. They’re fighting for better living conditions within New York City, better education. This is also the time where we have a lot of xenophobic immigration laws.

What were some of the surprising parts of your research?

[These immigrants] are also still heavily involved in the politics of home—the political climate of the Caribbean, and what’s happening there. Globally, they’re also really invested in what’s happening in Africa. One of the key points that I look at is 1935 when Italy invaded Ethiopia; at this time, Ethiopia is the only country on the African continent that’s not colonized by European power. The whole African diaspora and all Black people around the world are looking at Ethiopia. And so these groups are raising money to send to Ethiopian troops. They’re sending supplies there. Some people are actually going to fight for the Ethiopian army. So not only are they invested in what was happening where they are, but they see themselves connected to Black people throughout the world.

How did you see those connections form through your research?

One of the things that I was really interested in is how Black identity is formed—even with my own family, we’re all Black, but there were differences. So how did they become Caribbean, because they start off as someone from Antigua or Jamaica, but then they become Caribbean in the U.S. At the same time, they’re also becoming Black, and they’re becoming African American. They’re living in the same neighborhoods with African American people, they’re in the same job positions.

What do you hope people take away from reading your book?

There aren’t a lot of books that study this early period of Caribbean immigration. We tend to talk about the period after 1960 when there’s this boom of migrants, but I’m really interested to show that there are Caribbean immigrants who were coming prior to that, who are part of the fabric of New York City history, of U.S. history. I’m excited this book is coming out during Black History Month, because we don’t always talk about Black migrants as part of that history. But they are. For instance—no one ever talks about Malcolm X’s Caribbean heritage and what that meant for him as a Black political leader in the U.S. I’m hoping that this helps people feel seen and represented in ways that they hadn’t been before.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.